REIMPOSITIONING OF CULTURE THROUGH THE REPARTRIATION OF AFRICAN ARTEFACTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Concept.

2.Cambridge Museum Of Archeology and Anthropology and the acquisition of the Collections.

3. Collections at MAA Cambridge

4.Repatriation and Reimposition of Artefacts.

5.The Repatriated Ugandan Artefacts By MAA and findings from the cultural and Historical Backgrounds.

6. Musical Instruments

7. Ceramics and Pottery

8.Fetishes.

9.Ornaments and Fabrics

10. Conclusion

11. Bibliography

12. Image Source

CONCEPT

The Europeans who were in African countries between 18th and 19th centuries collected a series of artefacts which to them were just considered simply artefacts as end in themselves. However, these Artefacts had particular cultural attributes and rituals attached to them. Taking them meant that there was a particular backslide in the cultural values and practices. Besides, the artefacts in the contemporary Africa could play a vital significance of cultural reference and the exploration of the pre-colonial history. Evidence to the pre-colonial history is limited due to the fact that the artefacts which could serve this purpose were stolen. Relics according to Abiodan Johnson Eniyandunni are national treasures and part of cultural heritage that must be protected. They are priceless objects that have survived from an earlier time. The disappearance or theft of many historical artifacts has led to the disappearance of many early cultures. [j. art crime 15,111,2016] The repatriation of the African Artefacts is meaningless if the cultural values and the history behind them are unknown by the Current people of Africa. Perhaps the European Museums and Galleries are obliged to take on clear research with the support of African researchers to deliver the findings of cultural and pre-colonial historical attachments of the Artefacts they had in possession for centuries to the owner countries. Dr Chika Esiobu wrote that «The importance of these artifacts coming back to Africa is not aesthetic, as that is the only use it is to Europeans and Americans. These artifacts form an integral part of the definition of the identity and personality of the African, battered by years of deliberate attempts to wipe out everything positive about the race. Africans, resident and in the Diaspora, have no knowledge of who they really are. They do not know and therefore cannot reconnect with the pre-slavery and pre-colonial African psychology.» This research explores the strategies of the Repatriation of African stolen Artefacts and Re imposition their cultural and historical attachments by Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), a case study of the repatriation of Relics to Uganda.

The Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and anthropology hold a number of collections of Artefacts and Photographs of the past histories of many African countries. Many of these were collected by early Missionaries and Explorers who were tasked by Britain to go to Africa and lay a foundation for colonialism through exploration and theological impersonation, among these include Rev. John Roscoe who was an Anglican missionary in East Africa. He had an upper hand in collecting works from Uganda where he spent 25 years and learnt about their culture. Sir Harry Hamilton Johnstone, Frank Rogers, John Gilbert Rubie, Ernest Balfour Haddon and Arthur Brian Fisher were also among the Europeans known for collecting African Relics during the Pre-colonial and the colonial Periods in Africa. «Collections have reached the Museum in many different ways. Some artefacts, in common with those in similar museums, were acquired in the aftermath of violence, as loot, or in other ways that would not be considered legitimate or appropriate today.» [mma.cam.ac.uk]. The statement highlights the fact that the MAA museum Acknowledges the claims that some of the relics they have in possession were attained through dubious ways and so returning them back as an answer to the requests from many Africans is a debt they should pay clear attention to.

In this study, we will explore and investigate how the Cambridge museum of archaeology and anthropology attained the relics from Uganda. The Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has tried to answer the call of the many African countries who would wish to restore their Artefacts. The Museum is known to be the first British Museum to return artefacts to their owner country, and that was Uganda in 1961. The Museum has laid various strategies to repatriate Artefacts to different African countries. «We want to put these objects back into the hands of people who made them meaningful… we want them to live again, not only as museum pieces but as part of Uganda public culture, ” said Professor Derek Peterson (History, Afro-American & African Studies) serving as principal investigator for the project and working with colleagues from both MAA and the Uganda Museum. [source: mma.cam.ac.uk] The study of the reimpositioning of culture through repatriation of African Artefacts focuses on the project of the MAA to reposition the artefacts they have had in possession for decades and how they work hand in hand with the owners of the relics to find out the Cultural attributes and their Historical significance. This study is to target the communities and Kingdoms in East Africa with a particular emphasis on Uganda, studying the reimposed relics and How the Museum has presented the preserved Culture and History behind them through research. A case study of the 2024 project of 'Repositioning the Uganda museum by Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

CAMBRIDGE MUSEUM OF ARCHEOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY AND ACQUISITION OF THE COLLECTIONS FROM AFRICA

Museum_of_Archeology_and_Anthropology, _Cambridge

The Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has been in place for over 140 years as a profound academic a and research centre through exhibiting the collections of artefacts from various Continents and Countries. Among the Collections include Relics, Photographs, Textiles and other Relics from all over the World. The Museum boasts of a collection of the Human Past history and Cultural relics all over the world. «Two million years of human history. One million artefacts. Countless astonishing stories.» [maa.cam.ac.uk] Downing St., Cambridge, CB2 3DZ, GB, London, UK.

'MAA, founded in 1884, reflected growing public and scholarly interest in archaeology and anthropology. The Museum curators were and are primarily Cambridge academics, and together with other University lecturers and research students, they made collections in the course of fieldwork. Archaeological finds, artefacts and art works were also donated by former Cambridge students, some were bought through auctions or the art market, and up until the 1950s it was common for museums to exchange objects and collections with other museums, often in different countries'.[source; maa.cam.ac.uk]

Museum of Archeology and Anthropology [source; 2024]

COLLECTIONS AT MAA CAMBRIDGE

Cambridge Museum of Archeology and Anthropology.

The Museum holds a series of collections from different countries and cultures. The Collections have been kept for decades in the museum custody, being exhibited for Cultural, academic and Research Purposes. Collections from Australia through Archaeological and Anthropological expeditions. In 1888 and 1899 Alfred Cort Haddon collected a number of Artefacts, Cultural objects and photographs. Captain James Cook, And Frank Rogers. In Africa, many collections were attained from Benin in Nigeria by Anthony Ashley Bevan and William Downing Webster in 1897, and others from Uganda by Rev. John Roscoe around 1861 and 1932 and Ernest Balfour Haddon.

REPATRIATION AND REIMPOSITION OF ARTEFACTS

Rose Mwanja Nkaale, formerly Commissioner for Museums and Monuments, Adebo Nelson Abiti, Principal Curator, Uganda Museum, and Louise Puckett of MAA examining a set of ngato, leather divination cards.

According to the MAA, «there will be considerations to the requests to repatriate material, and will do so on a case-by-case basis. MAA will engage with Indigenous representatives and other interested parties in an honest and respectful way, and embraces an open and responsive approach to questions around the future care, circulation and destinations of cultural property administration, many Claims by the African countries too.» [maa.cam.ac.uk]. Depending on this particular response by the MAA, requests to restore the collected Artefacts have been Responded to and the Museum Acknowledges the fact that there is need to Liaise with the Indigenous people to Find Out Particular attachments of these artefacts in the Cultural and Historical Perspectives.

THE REPATRIATED UGANDAN ARTEFACTS BY MAA AND FINDINGS FROM THE CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDS Relics Of Uganda, their Cultural Attachments and History From Findings After the Repatriation.

Reverend John Roscoe, Anglican missionary with the Church Mission Society in Uganda, 1894-1909. Sir Apolo Kaggwa, (Prime Minister) of the of the Kingdom of Buganda. Photograph by Elliott & Fry.

The Artefacts from Uganda were attained by the Cambridge Museum Of Archaeology and Anthropology through the Christian Missionaries and Explorers who came to the East African Coast In the Late 18 and Early 19th Century. Rev John Roscoe an Anglican Missionary Collected a series of Artefacts from the Kingdoms and native Societies Of Buganda, Ankole, Toro, Bunyoro, Acholi and the Bagesu among others. And he cleary made an outstanding study through writing about the culture, beliefs and practices of the societies in Uganda, these are found in his books The Baganda- an account of their native customs and beliefs, The northern Bantu, Tribes Of Uganda protectorate and the Banyoro Kitara. , an account many Other relics were collected by the Ernest Balfour Haddon, an Irish-born British Administrator in Uganda, by then a colony of Britain.

Ernest Balfour Haddon, Irish-born British colonial administrator in Uganda, 1905-1945, and an unnamed man holding elephant tusks. MAA N.59174.EBH

«These artefacts were acquired in various ways: through confiscation, conversion, theft, gift and purchase. Most were brought by the Anglican missionary Reverend John Roscoe. But several were donated to the Museum by Apolo Kaggwa (sometimes spelled Apollo Kagwa), the Katikiro (Prime Minister) of the Kingdom of Buganda. Other donors include British colonial officials Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston, Ernest Balfour Haddon, Frank Rogers, and John Gilbert Rubie, and Anglican Missionary Arthur Bryan Fisher”[source; maa.cam.ac.uk]

Musical instruments

‘Mujjaguzo’ The royal Drum These Drums were 93 In total supplied to the local chiefs by the Kabaka (king) In Buganda kingdom.

‘Mujjaguzo’ The royal Drum These Drums were 93 In total supplied to the local Chiefs and were to beaten by the orders of king or may be the Chiefs, this was done incase of the need to announce the coronation of the new King ‘Kabaka», announce the death of the King’s Children or wives, victory in war or when the king entered a new Home. «Among the musical instruments of the Baganda drums must be given the first place. The drum was indeed put on the multitude of uses, quite apart from music; it was the instrument which announced both Joy and sorrow, it was used to let people know of the happy event of birth of children, and it announced the mourning of the dead. It gave an alarm for war and announced the return of the triumphant warriors who had conquered in war.» [The Baganda; General survey of the country, life, and Customs. John Roscoe, 1861-1932, Page 25] Indeed the Drum was a clear means of communication before the modern forms of communication came to Buganda, they already had a solution to communicate the messages in various situations. There is a myth of the format of dramming incase there was a social gathering among the ancient Baganda the ''Sagala agalalamidde drum sound '' which meant ''I don’t want any one sleeping at this juncture'', and all people would gather to understand the reason for the call.

Royal drum of the Bunyoro Kingdom. Banyoro People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.315.

Royal drum of the Bunyoro Kingdom Detailed Images with fetishes. Banyoro People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.315.

From John Roscoe’s 1915 publication 'The Northern Bantu: An Account of some Central African Tribes of the Uganda Protectorate. Cambridge: University Press', pg. 87: «Inside the drum, however, is a fetish [power object]. This may be only a small object, like a ball of medicated clay, or a stick to which a number of objects are fastened, but over the fetish the blood of some victim is poured; in the case of royal drums it is the blood of human beings who are decapitated over the drum for the purpose.».

Wooden zither, Ankole/Bahima People. Collected by John Roscoe E 1907.235. [source, MAA]

Wooden zither, and Thumb nail notes attached to the specimen. Ankole/Bahima People. Collected by John Roscoe E 1907.235. MAA

Some of the Musical Instruments played in Uganda were not Only for Entertainment but also Intimacy, Women among the Bahima and the Banyankole of Western Uganda were given this musical Instrument to play it privately for the Husbands during Romantic moments and this was believed to strengthen the marriage and increase the love of the couples. ‘an excellent specimen of this instrument formerly used by the women of the Bahima tribes of Uganda. It was obtained for the Cambridge Anthropological Museum by my friend, Rev. J. Roscoe. In the shape of the wooden sounding-board the original tortoise type survives’ [Ridgeway, William (1908). The Origin of the Guitar and Fiddles. Man, Vol. 8, pp. 17-21]

Musical Instrument.Bagesu People .Uganda.Collected and Donated by Rev John Roscoe.ROS.1920.239

Musical Instrument.Bagesu People and Details confirming the collector .Uganda.Collected and Donated by Rev John Roscoe.ROS.1920.239

Ceramics and Utensils

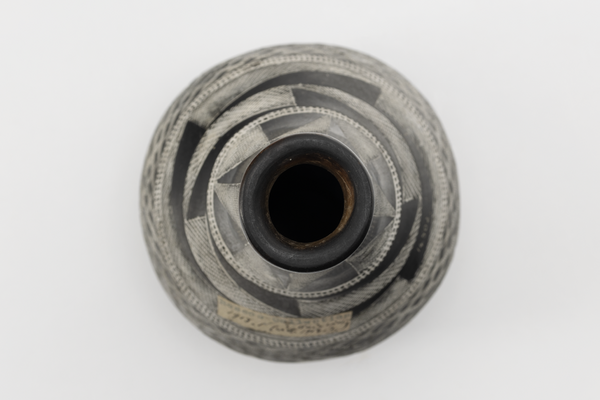

Lubale. Deity Vessel, E1907303, Roscoe John, Buganda.Ceramic Pottery[Cambridge MAA]

Clay vessel associated with Lubaare. Obtained from chief Kimbugwe, former keeper of the Balongo. Baganda People. Collected by John Roscoe. E 1907.303

This pottery vessel was dedicated to Lubaale, a globular round vessel with eight spouts coming from the main body of the vessel. It was used to give the criminals drugged alcohol or any other drink or may. However, the small bag of pottery that was used also helped in giving herbs in the beer to the criminals before their execution. This was done in order to give power to the king over their ghosts, since sometimes they could come back demanding justice.

Ceramic milk bottle.detailed in different views Ankole/Bahima people. Collected and donated by John Roscoe. E 1907.205

'Milk Pot made from black earthenware. Conical with a long tapering neck, everted rim, and small pedestal base; decorated with incised designs filled with white pigment; three horizontal bands with raised dots alternating with triangles filled with hatching, vertical bars, and grid motif; burnished' [Katrina Dring, maa.ac.uk] These are domestic utensils used by the people of Ankole and the Bahima to store milk after milking the cattle. Besides, the smaller ones were used to keep the cow ghee. Serving milk to their neighbors who were close and those who were distant, it was covered by the banana plant fibers.

Milk Pot made from black earthenware.

Milk Pot made from black earthenware.Uganda.Collected by Roscoe.

Many functional objects were made by the Africans, like pottery and ceramics. Many of these were decorated depending on the particular need of the potter! In traditional African society, each family had a particular craft that they were practicing. The skills of pottery, weaving, blacksmithing, and many others came as a result of activity inheritance from their parents and great-grandparents! Potters always designed their milk pots to look more beautiful and pleasing; black and white pigments were made, some of them were fired while others were just colored. It should be noted that the traditional Africans created most of their crafts for functional purposes. Ornamental crafts were also highly observed for women, men, and children.

Ornaments and fabrics

Etok. Headdress of human hair. Acholi People. Collected and donated by John Gilbert Rubie. 1937.924.1-2 A

Africans were also renowned for designing and decorating fabrics and Ornaments which were specifically to enhance the beauty of the people. Women in some societies were the ones specifically creating the ornaments among their main activities. Every particular society Had their own ornaments worn by various people on different occasions like Initiation of the teenagers, marriage, and leaders like Kings and chiefs had their own particular ornaments and clothes.

Etok. Headdress of human hair. Acholi People. Collected and donated by John Gilbert Rubie. 1937.924.1-2[maa.ac.uk]

Etok Head Pad- Acholi Chief

''Materials identified by curator Nelson Abiti and colleagues at the National Museum of Uganda in consultation with the Uganda Wildlife Authority and other experts in the field. Human hair, Glass beads, Feather and bone support- possibly common ostrich (Struthio camelus), Plant fibre bindings- East African highland banana, Ox hide discs- Sanga’ cattle (Bos taurus africanus), Forwarded by Derek Peterson, Ali Mazrui Collegiate Professor of History & African Studies, University of Michigan, as part of the Repositioning the Uganda Museum.[maa.ac.uk]

Ornament of human hair. Acholi People. Collected and donated by Frank H. Rogers. Given to him by Olia, chief of the village of Atiak. 1927.1523

This headpad was designed from the human hair given by the actual owner, or maybe the rest of the men would sacrifice their own hair so that it may be used to design the one for the chief. It was a headdress worn by the serious men in the village during celebrations and festivals. However, the men surprisingly shaved off all their hair and remained bald before wearing this headpad. It always happened when there was a traditional festival during the dance and sometimes when the men wanted to bless themselves with a day well styled. «…the pad of hair, which is closely matted with a circlet of white strips cut from cowrie shells (originally teeth, human or goat), and into the center of the pad is sewn a pig’s tusk.» [source: maa.ac.uk]

Ornament of human hair. Acholi People. Collected and donated by Frank H. Rogers. Given to him by Olia, chief of the village of Atiak. 1927.1523 B

Ornament of human hair. Acholi People. Collected and donated by Frank H. Rogers. Given to him by Olia, chief of the village of Atiak. 1927.1523 B The same purpose as the one we talked about previously in the ''Boar Shape» but this one is presented in the ''Cone Shape»

Ddamulo. Staff of office of the Katikiro of the Kingdom of Buganda. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.256.

'Ddamula. Official staff of the office of the Katikiro (Prime Minister). Wooden staff with a widened, conical, brass-topped head with a fringe of small, conical brass bells. The staff is bound at intervals with five sections of copper wire, and it flares out slightly at the base. Originally there were eight bells around the top; there are now only five.' Africa; East Africa; Uganda, collected and donated to MAA by Rev. John Roscoe [maa.ac.uk]

Ddamulo. Staff of office of the Katikiro of the Kingdom of Buganda. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.256.

Ddamula -The Katikkiro’s rod (stick)

The Katikkiro is the prime minister in the Buganda Kingdom Government who was appointed by the Kabaka (king) by handing him the Ddamula Stick (rod) so that he may rule over the kingdom on his behalf, known as «Okulamula». With this Ddamula Stick, the Katikkiro would carry out his duties of organizing the Lukiiko (Royal Parliament) and monitoring the duties of the county chiefs (Abataka) who represented their counties (Amasaza) at the Lukiiko as leaders. Besides that, the Katikkiro was in charge of overseeing the royal assets, «Ebyobugagga» and the treasury ''Eggwanika». This Ddamula stick as a royal symbol of authority was given to the Katikkiro during the coronation ceremony.

A kanzu, the traditional formal dress of Muganda man. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.59

A kanzu, detailed visuals of the upper and lower part and sleeve. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. ROS 1920.59

The Kanzu, The traditional formal dress of the Muganda man is worn on almost all the occasions, even at home, just changing the nature. The kanzu was designed using linen with a full length. The kanzu had a detail of the Muleera design in the lower part (middle image), which made it attain the name of «Ekkanzu y’omuleera,» Ekkanzu y’omuleera» meaning the kanzu embedded with a Muleera design! Mostly designed in White, off-white, and sometimes brown.

Fetishes

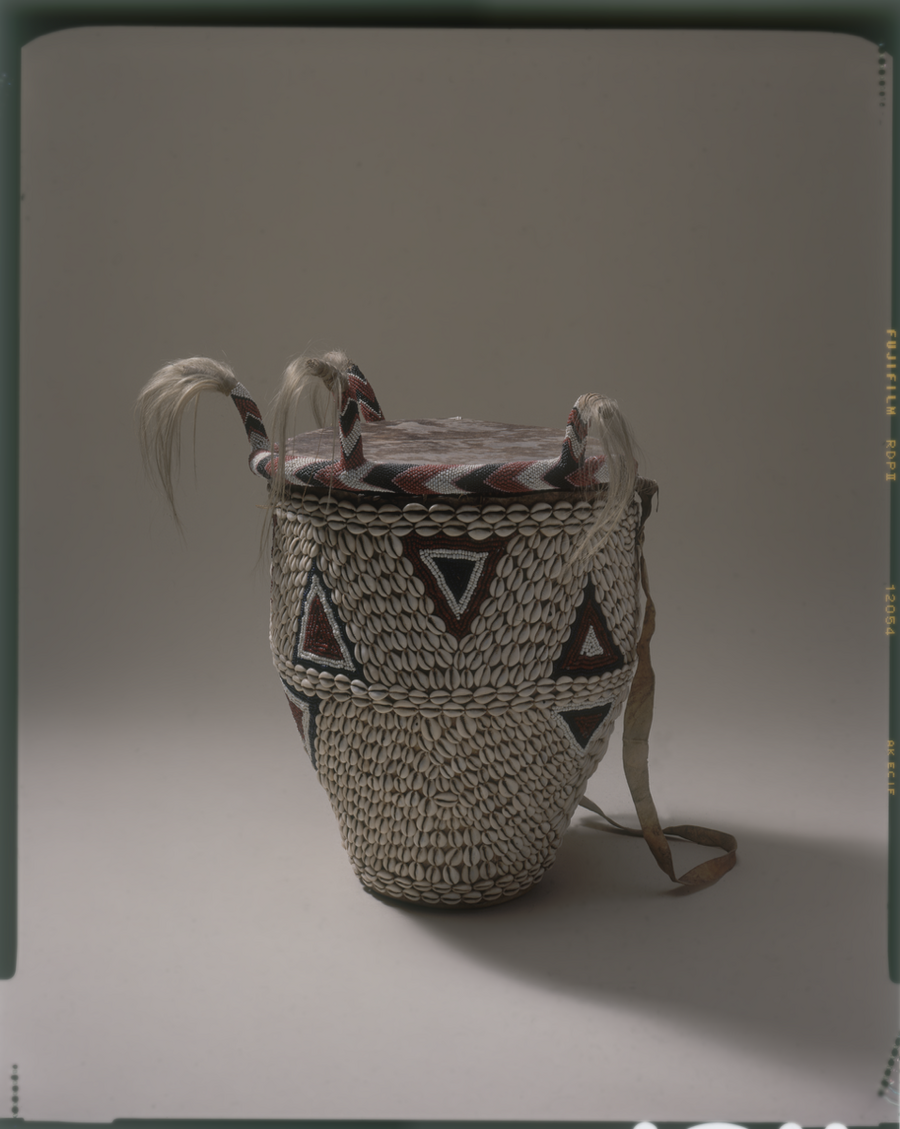

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Donated by Sir Apolo Kaggwa. E 1903.473.

Africans in the traditional African Society had a religion before the coming of the christian Missionaries into East Africa. Religion was part of the traditional culture of Africans, Greeting, respecting elders, Worshiping and practicing of the of the morals. Besides the Africans Knew God and gave God various names and attributes like Among the Baganda of central Uganda God is known as «Katonda» (means creator) and «Ruhanga» (means the maker of everything) among the Banyankole and the Bahima both in western Uganda. This fact is opposed by the European Christian Missionaries who came to East Africa claiming that it is a continent that knew nothing about God and Perhaps they claimed ''We introduced the knowledge about God to Africa». The ststement isnt true basing on the clear evidence about the knowledge of religion in the continent.

Prof. John S. Mbiti (1931-2019) African Religions and Philosophy, published in 1969, wrote: ''Although many African languages do not have a word for religion as such, it nevertheless accompanies the individual from long before his birth to long after his physical death. (…) Chapters of African religions are written everywhere in the life of the community, and in traditional society there are no irreligious people. To be human is to belong to the whole community, and to do so involves participating in the beliefs, ceremonies, rituals and festivals of that community.''

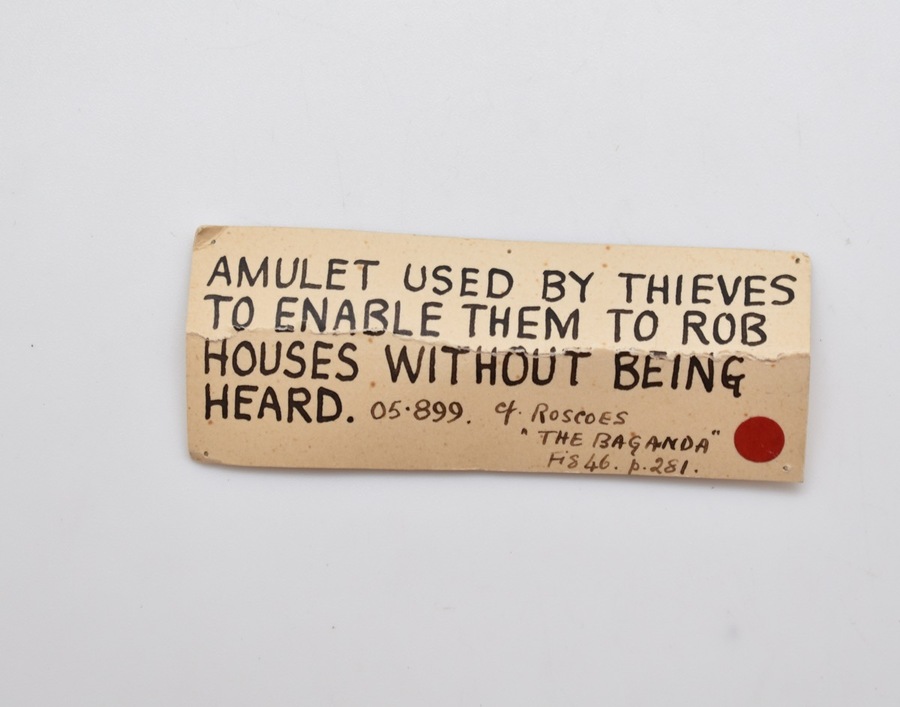

The statement highlights the truth about African Traditional religious beliefs ceremonies, rituals and festivals. All these required the Use of religious Objects and Fetishes. However some people were attached to witch craft and divination with aims of revenging, Punishing criminals and Traditional medication. In this last section of the Repatriated Artefacts to Uganda we will explore the Fetishes and religious Objects used by the traditional ugandan people to worship and Carry out other spiritual activities like witchcraft, sorcery, foretelling and divination.

A set of eight leather ngato (divination cards), used to obtain the decision of the god Mwanga. Baganda people. Collected and donated by John Roscoe. ROS 1920.479.1-8

'Ngato. Leathers for throwing to obtain the decision of the god Muwanga.' Added in second hand: 'They are eight in number, flat and rectangular in shape, one end being corrugated.'[source; mma.ac.uk] Ngato divination cards were used by the traditional foretellers to practice divination. they were thrown to determine the decision of the ancestral god Muwanga. The Ngato fortune tellers were regarded to be the final diviners when all the diviners and medicine men had failed. They even had a saying that ''Bwolemwa ebyange ogenda ku wa ngato'' (Luganda), translated as ''If what i told you has failed you will have to go to the Ngato diviners.''

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. E 1904.350

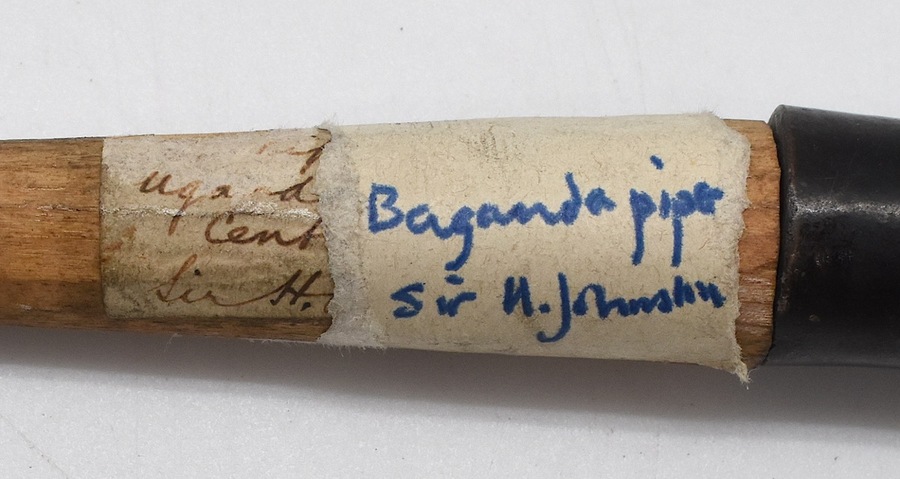

Emmindi, Clay tobacco pipe. Baganda People? Collected and donated by Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston. E 1901.252

Clay tobacco pipe. Baganda People? Collected and donated by Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston. E 1901.252

''A pipe with a black clay bowl and wooden stem. The bowl is a truncated square pyramid shape, narrower at the bottom and flaring out towards the rim. The four edges of the rim are curved and concave, and the corners are pointed up. The bowl is decorated with alternating red and white lines and very fine incised cross-hatching, and the cylindrical stem also has a red and white linear design. The top of the stem is made of wood, and it tapers in towards the top. Three of the bowl’s four corners are chipped, and there are splashes of white paint on the bowl. [Source: maa.cam.ac.uk] Traditionally known as «Emmindi», the windpipe was used by the mediators and diviners who smoked it with a drug during the worship time, which is traditionally known as «Okusamira» done for the idols and the spirits. They always smoked tobacco burnt with a piece of burning charcoal.

MAYEMBE CHARMS AND FETISHES Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. MAA.

'Fetiches (mayembe) were a miscellaneous assortment of fetishes, objects of all sizes and shapes. They were the nearest approach to idols, and indeed they correspond to a large extent to the idols of other tribes of Africa. Some of them were entire horns of antelopes or of buffaloes, while others were only the tips of horns of small antelopes, not more than two inches long. In each case the hollow of the horn was filled by the medicine men with herbs, clay, and other substances, and the open end was stopped and decorated, sometimes with a wooden plug studded with pieces of brass or iron. Sometimes a small round hole was made in the fetish, a little more than a quarter of an inch in diameter and half an inch deep; often this hole was in the plug at the end. The horns were thought to have become vehicles of the god by whose name they were called and whose powers they were supposed to convey to those who owned them. The small hole made in them was the place into which drugs or medicines were poured, either for internal or external application, as directed by the medicine man; the drugs were supposed to convey the powers of the god by being poured into the fetish, in addition to having their own healing properties. Under ordinary circumstances the mere possession of the fetish was enough to ward off evil from the house and to ensure blessing; hence they were kept in numbers in a special place in each house and had drink placed daily before them by the owner’s wife. Other fetishes were made of wood or of clay mixed with other substances in a manner known to the medicine men only. These latter fetishes were molded into different shapes, and each kind was known to the people by its shape and size; some of them were kidney-shaped, others were crescents, while others were large discs with a hole in the center.' [Source: John Roscoe, The Baganda: An Account of Their Native Customs and Beliefs (Macmillan, 1911), 279]

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Donated by Sir Apolo Kaggwa. E 1903.473

'Jjembe. Power object. Two objects attached to a twisted double-fiber cord. One of the objects is larger than the other; it is circular, has a leather cover stitched to the exterior, and features three canine teeth inset into holes; possibly more teeth were present at one point. The smaller object is crescent-shaped and has a woven fiber cover; underneath a stitched leather cover is visible'. [maa.cam.ac.uk]. This fetish (Jjembe) was used by the Baganda people with the aim of attaining protection from the ancestral god Mukasa. However, besides protection, they as well used it to dedicate their animals to be protected from being struck by lightning.

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Donated by Sir Apolo Kaggwa. E 1903.471.

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Donated by Sir Apolo Kaggwa. E 1903.478).

Jjembe (fetish), a power object created in a long stick format with a folded globular projection on its tip, may contain the charms. It is twisted using banana fibers (ebyayi) from the banana plantation.

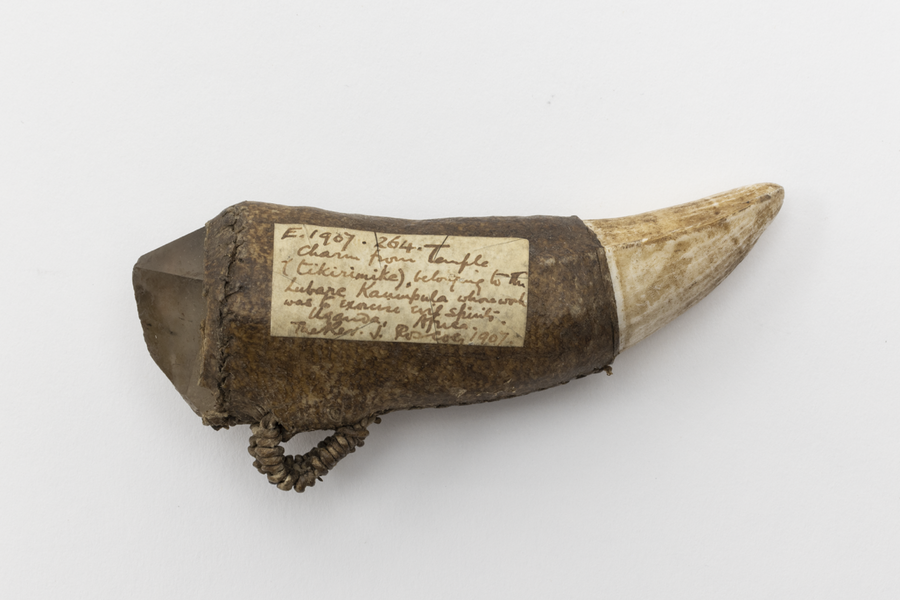

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Collected and donated by Reverend John Roscoe. E 1907.264

Tikirimikie. A charm created with a hide, crocodile tooth, and a rock inside, the hide is fastened on the forepart, and the rock is tightly enclosed. This Jjembe is attributed to Lubale Kawumpuli. The main purpose of this Jjembe fetish is exorcism of the evil spirits. This clearly shows that in traditional African society there existed both good and evil spirits, which came with danger against the people in the society, and the so-called good spirits like Kawumpuli were used to exorcise the evil ones. Africa; East Africa; Uganda, Buganda.

Jjembe. Power object. Baganda People. Donated by Sir Apolo Kaggwa. E 1903.476.

'Materials identified by curator Nelson Abiti and colleagues at the National Museum of Uganda in consultation with the Uganda Wildlife Authority and other experts in the field. Barkcloth- Fig (Ficus natalensis, aka Mutuba); Skin/fur- likely to be greater cane rat (Hyonomys swinderianus); Hide cord ’cattle (Bos taurus africanus); Plant fiber bindings- East African highland banana (Musa acuminata colla).' Forwarded by Derek Peterson, Ali Mazrui Collegiate Professor of History & African Studies, University of Michigan, as part of the Repositioning the Uganda Museum project [source: maa.cam.ac.uk].

Drum dedicated to Dungu, god of the chase. Baganda People. ROS 1920.31. MAA

This drum is not Just a musical instrument like other drums, it was a fetish dedicated to Ddungu an ancestral god attributed to hunting and providence. Within the drum was another fetish Jjembe power Object which was removed by Rev. John Roscoe who cut the Drum while still in Uganda. The jjembe removed is shown in the figure below.

jjembe (power object) inside was removed. ROS 1920.375 MAA

Rachel Hand, Collections Manager for Anthropology at MAA, with Solomy Nansubuga and Alice Nanyombi assessing the condition of returned artefacts on arrival at the Uganda Museum, 10 June 2024[maa.cam.ac.uk]

All the artifacts and relics presented in this research were among the 32 relics in the collection that was repatriated by the Cambridge Museum of Archeology and Anthropology to Uganda in the project known as the «Repositioning of the Ugandan Museum,» which happened on Saturday, 8 June 2024, in Uganda!

CONCLUSION

The relics presented by the Cambridge Museum of Archeology and Anthropology to Uganda through the project of the «Repositioning of the Uganda Museum» are physical relics; however, the clear understanding of the culture and history behind them was the main purpose of this research, and we have been able to attain the actual names, the knowledge, theories, and history behind all these artifacts. All the relics have been investigated, and findings served in the most descriptive visual way possible. The study represented all the major regions of Uganda: Central (Buganda), East (Bagisu), West (Banyankole, Bahima, and Banyoro), and North (Acholi) were observed. Cultural practices and beliefs have been opened up by presenting the artifacts in line with entertainment, leadership, domestic life, ornaments and fabrics, and finally the religious relics. Described through the expression of their names, nature, purpose of their creation, and history behind them. Culture is reimposed through the deep investigation of the repatriated relics and artifacts.

A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots. _ Marcus Garvey

Johnson EniyandunniJ.Marginalized Voices: Returning Historical Artifacts to the Origin: A Critical Examination of Cultural Heritage Art Crime 15, 111, 2016

Chika Esiobu .Returning African stolen Artifacts (i) first published by News Africa London 2008

Cambridge museum of Archaeology and Anthropology https://maa.cam.ac.uk/about/our-approach-return-museum-Objects 2024.

Cambridge Museum Of Archaeology and Anthropology.https://www.returningheritage.com/maa-cambridge-repositions-its-relationship-with-ugandan-artefacts,2024.

5.Cambridge Museum of Archaeology anthropology https://maa.cam.ac.uk/repositioning-uganda-museum2024

Rev. John Roscoe.The Baganda; an account of their native customs and beliefs 1861-1932

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, The Journal, Vol.37, pp.93118.https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.537261/page/n43/mode/2up

Ridgeway, William (1908). The Origin of the Guitar and Fiddles. Man, Vol. 8, pp. 17-21https://zenodo.org/records/1643459

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Museum_of_Archeology_and_Anthropology,_Cambridge.jpg (25.11.2025)

«Elliott & Fry». PhotoLondon. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. (22.11.2025)